Table of Contents

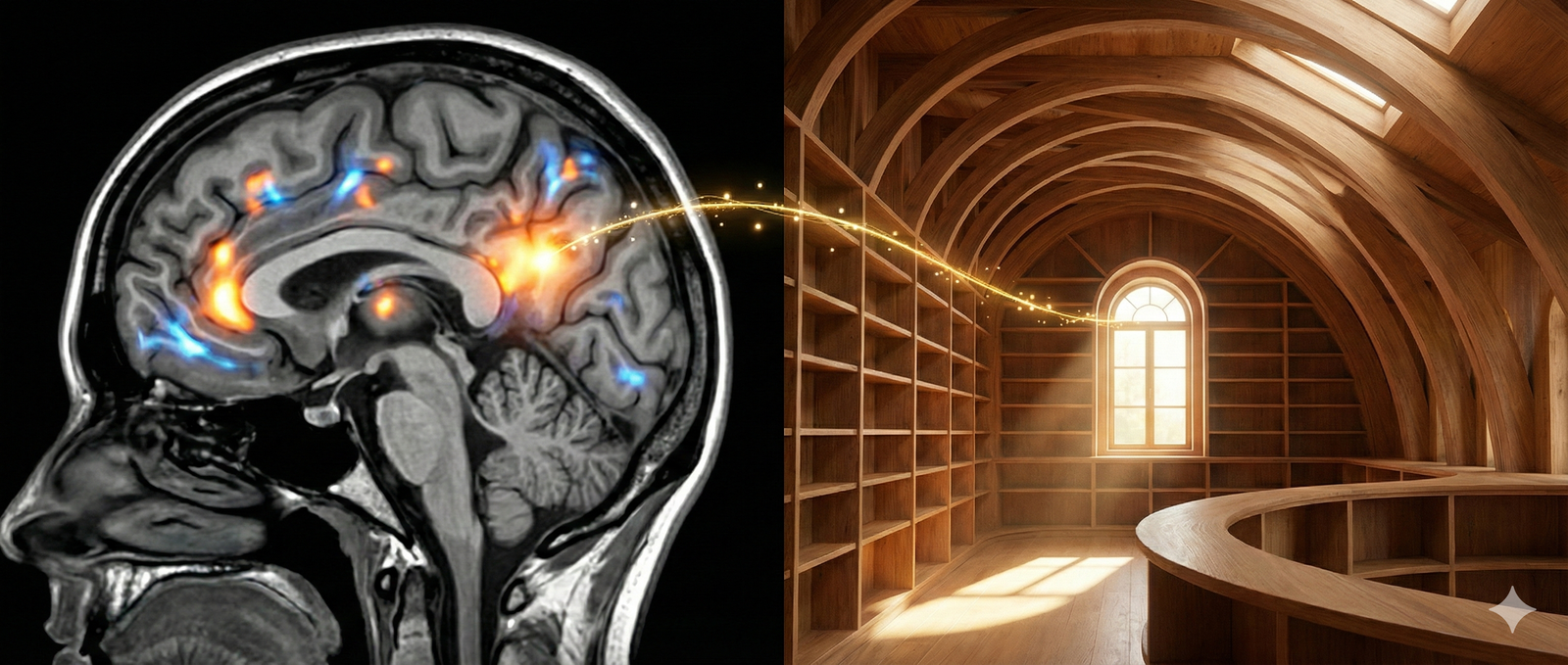

Have you ever walked into a cathedral and felt a sudden, inexplicable sense of awe? Or sat in a hospital waiting room and felt your anxiety spike, not just because of why you were there, but because of the buzzing lights and the sterile smell?

For centuries, architects have relied on intuition to create these feelings. They felt that high ceilings inspired grandeur and that cramped, dark rooms caused unease. But they couldn’t prove it. They didn’t know what was happening inside the neurons of the people inhabiting their spaces.

Today, that has changed. We have entered the era of Neuroarchitecture.

Neuroarchitecture is the intersection of neuroscience and the built environment. It uses mobile brain imaging (EEG), virtual reality (VR), and biometric sensors to measure exactly how the brain responds to architectural stimuli. It moves the conversation from “I think this looks good” to “I know this lowers cortisol.”

In this groundbreaking guide, we will explore the science behind the spaces we inhabit. We will uncover how ceiling heights change the way you think, why your brain loves curves, and how we can design buildings that actively make us happier, smarter, and healthier.

What is Neuroarchitecture? The Bridge Between Brain and Building

Neuroarchitecture is not a style; it is a feedback loop.

Traditionally, architecture was a one-way street: the architect designed, and the user adapted. Neuroarchitecture asks: How does the user’s physiology change in response to the design?

It is rooted in the discovery of Adult Neuroplasticity—the fact that our brains are constantly reshaping themselves based on our environment. A famous study in the 1990s showed that taxi drivers in London had enlarged hippocampi (the part of the brain responsible for spatial memory) because they spent years navigating the complex city.

If a city can change the physical structure of your brain, imagine what your home or office is doing to you after 10 years.

The Tools of the Trade

How do we measure this?

- fMRI & EEG: Scanning the brain to see which areas light up when a subject looks at a sharp corner vs. a curved wall.

- Galvanic Skin Response (GSR): Measuring sweat gland activity to detect hidden stress levels.

- Virtual Reality (VR): Placing subjects in a virtual building and modifying the walls in real-time to see how their heart rate responds.

The Science of Space: 5 Key Findings

Research in Neuroarchitecture has already yielded surprising results that challenge traditional design wisdom.

1. Ceiling Height Affects Thinking Style

Does a low ceiling make you focus? Yes.

- The “Cathedral Effect”: Research shows that high ceilings trigger abstract, creative thinking. When we are in a voluminous space, our brains are primed for “big picture” ideas.

- Low Ceilings: Conversely, low ceilings foster concrete, detail-oriented thinking. If you are designing an operating room or an accounting firm, you might actually want lower ceilings to encourage focus on the task at hand.

2. Curves vs. Corners (The Amygdala Response)

Humans have an innate preference for curves. When subjects are shown sharp, jagged interiors, their amygdala (the brain’s fear center) lights up. Sharp corners trigger a subtle “threat” response—likely an evolutionary holdover from avoiding sharp rocks or thorns. Curves, on the other hand, activate the anterior cingulate cortex, a region associated with emotion and pleasure. Designing with organic forms isn’t just an aesthetic choice; it’s a way to lower the collective blood pressure of the building’s occupants.

3. Wayfinding and the Hippocampus

Getting lost is stressful. But in many hospitals and airports, getting lost is guaranteed by design. Neuroarchitecture emphasizes “intuitive wayfinding.” When a building has clear landmarks and distinct visual zones, the hippocampus can easily build a “cognitive map.” When the floor plan is a repetitive maze (like many hotels), the brain releases cortisol (stress hormone) as it struggles to orient itself.

- Design Fix: Use unique art, color coding, or distinct architectural features at key intersections to serve as “breadcrumbs” for the brain.

4. Light and the Circadian Rhythm

We have sensitive photoreceptors in our eyes (ipRGCs) that have nothing to do with vision and everything to do with time. They tell our brain when to release melatonin (sleep) and when to release serotonin (wake). Most offices have static lighting that confuses these receptors, leading to insomnia and depression. Neuroarchitecture advocates for “Dynamic Lighting” that mimics the sun’s arc—bright blue-white in the morning for alertness, and warm amber in the evening for relaxation.

Designing for Healing: The Hospital of the Future

Nowhere is Neuroarchitecture more critical than in healthcare.

The “standard” hospital design—long corridors, fluorescent lights, lack of privacy—is actually toxic to the brain. It induces “ICU Psychosis,” a delirium caused by sensory deprivation and stress.

The Cleveland Clinic Example

Leading hospitals are now designing “Empathetic Buildings.”

- Views of Nature: Studies prove that viewing nature reduces pain perception. New hospitals ensure beds face windows, not walls.

- Acoustic Control: Noise is the #1 stressor in hospitals. Sound-absorbing materials are used to dampen the beeping of machines, allowing patients’ brains to enter restorative sleep cycles.

- Control: Giving patients control over their environment (dimming lights, changing temperature) restores a sense of agency, which is a powerful antidepressant.

Designing for Learning: The Classroom Brain

Schools are often designed like prisons: hard surfaces, straight lines, and strict control. Neuroarchitecture suggests this kills learning.

- Enriched Environments: A famous study on mice showed that those raised in “enriched environments” (toys, tunnels, textures) had 25% more synapses in their brains than those in “impoverished” cages.

- Application: Schools need sensory richness—texture, color, and complexity. A sterile white classroom provides no stimulation for neural growth. Flexible seating and varied learning zones engage different parts of the brain, catering to different learning styles.

The Future: The Sentient Building

As Neuroarchitecture matures, it is merging with AI.

We are moving toward buildings that “read” the room—literally. Imagine an office that detects (via cameras or wearable sensors) that the collective stress level of the team is rising. The building responds by:

- Lowering the ambient temperature slightly.

- Adjusting the lighting to a calmer hue.

- Playing subtle biophilic sounds (running water).

This is the ultimate goal: a symbiotic relationship between the biological brain and the architectural body.

Conclusion

Neuroarchitecture teaches us that we are not passive observers of our environment; we are active participants in a biological dialogue with it. Every wall you build, every window you place, and every light you install triggers a chemical reaction in someone’s brain.

For architects, this is a heavy responsibility, but also an incredible opportunity. We have the power to design buildings that don’t just shelter us from the rain, but shelter us from stress. We can design homes that heal, schools that inspire, and offices that invigorate.

The blueprint of the future is not drawn on paper; it is drawn on the mind.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

-

Is Neuroarchitecture a recognized science?

Yes. It is an interdisciplinary field supported by the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture (ANFA), founded in 2003. It combines neuroscience, psychology, and architecture.

-

Can Neuroarchitecture treat mental illness?

It cannot “cure” illness, but it can act as a powerful co-therapy. “Therapeutic Architecture” is used in psychiatric facilities to reduce aggression and anxiety in patients, reducing the need for sedation and restraints.

-

Does Neuroarchitecture only apply to modern buildings?

No. In fact, many ancient buildings (like Greek temples or Gothic cathedrals) accidentally mastered Neuroarchitecture principles (symmetry, fractal patterns, high ceilings) which explains why they have remained beloved for centuries.

-

How can I apply Neuroarchitecture in my own home?

Start with decluttering (visual chaos spikes cortisol). Introduce curves in your furniture (round tables, soft sofas). Maximize natural light during the day and switch to warm, dim lamps (no overhead lights) after sunset to protect your sleep cycle.

-

Is it expensive to design with Neuroarchitecture?

Not necessarily. Many principles—like allowing natural light, using color psychology, or arranging furniture to promote social interaction—cost nothing extra. It is about decision-making, not just expensive materials.